Most people expect some aches and pains as they get older, so you might not be surprised if you’ve started waking up with aching or stiffness, say, in your shoulder and upper arms. However, if the pain isn’t going away, there could be an underlying disease at play.

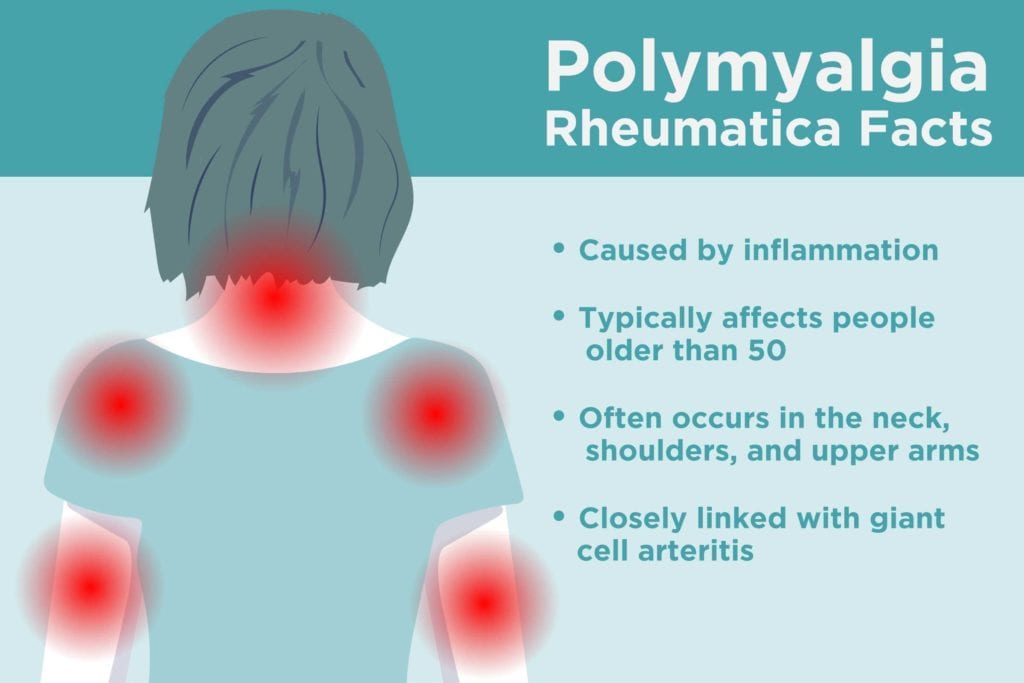

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is believed to be an autoimmune disorder (where the immune system attacks normal cells within the body). “Poly” means “many” and “Myalgia” is Greek for “muscle pain.” In PMR, the immune system causes inflammation in the joints and connective tissues leading to aches and pains in the surrounding muscles.

PMR typically affects people older than age 50 and is more common in women than men. PMR is treatable and can go away with proper treatment, though it might take years to get rid of symptoms completely. Read on to find out what to expect from symptoms, diagnosis, treatment and more.

Causes of Polymyalgia Rheumatica

Its exact cause of PMR is not known, but it can be influenced by environmental factors, such as an infection.

Age is a big risk factor — almost no one under age 50 gets PMR, and, according to a BMJ review, the likelihood of getting it increases with age. The average age when PMR symptoms start is 70.

Women also have a higher risk of polymyalgia rheumatica; about three quarters of PMR patients are female. Genetics could also play a role. People of northern European descent have a higher risk than other ethnic groups.

Symptoms of Polymyalgia Rheumatica

The symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica tend to start abruptly — sometimes overnight — though they can also develop over time. “Pain in polymyalgia rheumatica is more localised to the neck, shoulders and upper arms, and then there’s a second region, which is the lower back, hips and thighs,” says Konstantinos Loupasakis, MD, a rheumatologist with MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington, DC.

Although there may be inflammation present in the body, polymyalgia rheumatica does not usually cause swollen joints This can make it harder to detect.

PMR pain tends to be mirrored on both sides of the body and is worse in the morning than at night. Vague secondary symptoms, like fatigue, fever and weight loss can accompany PMR too. The pain and stiffness can make it challenging to sleep well and cause difficulty getting dressed or doing household chores.

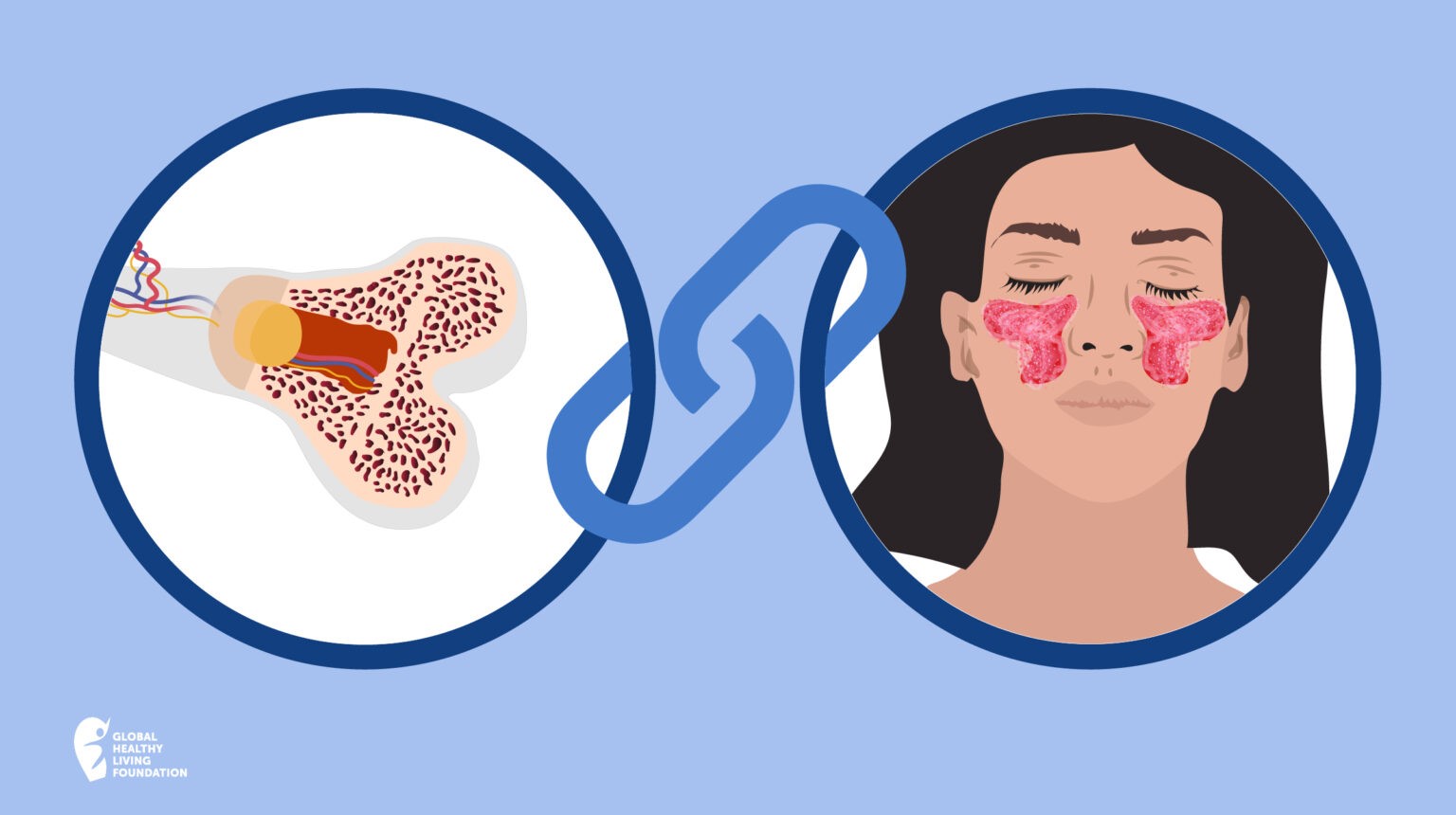

There is a close link between polymyalgia rheumatica and a type of blood vessel inflammation called giant cell arteritis (GCA). Up to half of all people with GCA have PMR, while about 10 per cent of those with polymyalgia rheumatica will also have giant cell arteritis. Giant cell arteritis symptoms, like headache, jaw pain and vision changes, can be additional clues that someone’s muscle pain is related to polymyalgia rheumatica.

PMR vs Similar Conditions

There’s no single test that clinches a PMR diagnosis, so figuring out what’s behind PMR symptoms can be tricky. PMR is often confused with fibromyalgia, which can also cause muscle pain in the shoulders and arms, and is far more common in women than in men.

However, there are some key differences between fibromyalgia and polymyalgia rheumatica. For one thing, the average onset age of fibromyalgia is 35 to 45, which is far younger than would be expected with PMR. The nature of the pain is also different — fibromyalgia develops when brain receptors start signaling pain without a trigger, while PMR is driven by inflammation.

This also sets it apart from wear-and-tear osteoarthritis. “The joints [from osteoarthritis] don’t really display much inflammation, such as warmth, swelling and increased blood flow,” says Dr Loupasakis.

Meanwhile, the placement of the pain — the shoulders and pelvic area — sets it apart from other types of inflammatory arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, which tends to show up first in smaller joints like the hands, wrists and feet adds John Davis III, MD, a rheumatologist with Mayo Clinic.

How Polymyalgia Rheumatica is Diagnosed

“PMR is a disease where history is very important,” says Dr Davis.

A rheumatologist will order blood tests like sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein (CRP), both of which measure general inflammation in the body without pointing to a specific body part or cause.

If there’s a high level of inflammation, and the symptoms and history match what would be expected of someone with PMR, doctors will likely start a course of corticosteroids, such as prednisolone. A good response to treatment helps assure rheumatologists that it’s the right diagnosis, says Dr Davis.

How Polymyalgia Rheumatica Is Treated

Almost all patients with polymyalgia rheumatica are treated with corticosteroids to ease inflammation in the body. “Patients with PMR respond extremely well to low doses of steroids,” says Dr Loupasakis. “Within the first three days they will notice improvement right away — usually within 24 hours.” Those with accompanying GCA generally need higher doses of steroids for the medication to take effect, he adds.

The treatment won’t work unless patients stick with it, but corticosteroids can have long-term side effects such as kidney problems, vision changes and increased blood pressure. That’s why doctors start PMR patients on as low a dose as possible to manage their symptoms, then gradually decrease the dose unless there’s a flare. “We try to taper the dose and keep it as low as tolerated,” says Dr Davis.

Meanwhile, patients might also start regimens like taking calcium and vitamin D supplements to prevent bone loss and other side effects of steroids. Most people with PMR can finish up steroids and be symptom-free after a year or two, but some might need to stay on medication for up to five years.

If you have PMR and suspect you could also have giant cell arteritis (red-flag symptoms include headache, vision changes and jaw pain), see a doctor right away. GCA can affect blood flow to the eyes and can cause permanent vision loss if left untreated.

Keep Reading

- Buttock Pain: Is Arthritis Causing It?

- Using Your Brain to Manage Your Pain

- 5 Ways Your GP Can Help You Manage Your Chronic Illness

This article has been adapted, with permission, from a corresponding article by Marissa Laliberte on the CreakyJoints US website. Some text and information have been changed to suit our Australian audience.