Like many types of inflammatory arthritis, psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is an autoimmune disease that affects your joints, causing pain, stiffness and swelling (as well as long-term damage). Men and women tend to develop PsA in equal numbers, and the first symptoms usually appear when people are between the ages of 30 and 50.

People commonly associate psoriatic arthritis with psoriasis, an autoimmune disease that affects the skin, causing flares of red, silvery plaques, although you don’t necessarily need to have psoriasis to develop PsA.

“Up to 20 to even 30 per cent of patients who have psoriasis will go on to develop psoriatic arthritis,” says Rebecca Haberman, MD, clinical instructor of rheumatology at the department of medicine, NYU Langone Health in New York City. “But it’s really only recently that psoriatic arthritis has come to the forefront of both rheumatology and dermatology. Dermatologists don’t always know all of the signs or the symptoms of psoriatic arthritis to know when to refer people to a rheumatologist.”

That helps to explain why some people with psoriasis aren’t readily diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis, says Dr Haberman. In fact, a 2015 study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology found that about 15 per cent of patients with psoriasis had undiagnosed PsA.

Misdiagnosing Psoriatic Arthritis: Why It’s Common

People with PsA may not have psoriasis or may not ‘realise’ they have psoriasis

In about 70 per cent of PsA cases, psoriasis symptoms come first. In about another 15 per cent, psoriasis and PsA symptoms strike at the same time and in another 15 per cent, the arthritis-like symptoms come first.

When patients don’t have obvious psoriasis symptoms, it can lead doctors to not suspect PsA, says Daytona Beach, Florida, rheumatologist and CreakyJoints medical advisor Vinicius Domingues, MD. “Patients have zero skin manifestations, but they have an inflammatory pattern of pain, and then just because they don’t have psoriasis, doctors don’t diagnose them with psoriatic arthritis.”

Or you may have psoriasis, but not realise or think about it much. “It’s not always easy to diagnose the psoriasis or see the psoriasis,” Dr Haberman notes. “Patients think, ‘Oh, I’ve had this one little area behind my ear that sometimes itches,’ but otherwise they never notice it. Or they could have a little fleck in their scalp, which they just think is dandruff.”

PsA has many different symptoms

Even taking skin manifestations out of the equation, “psoriatic arthritis is a very complex, heterogeneous disease. It can present in many different ways,” Dr Haberman explains.

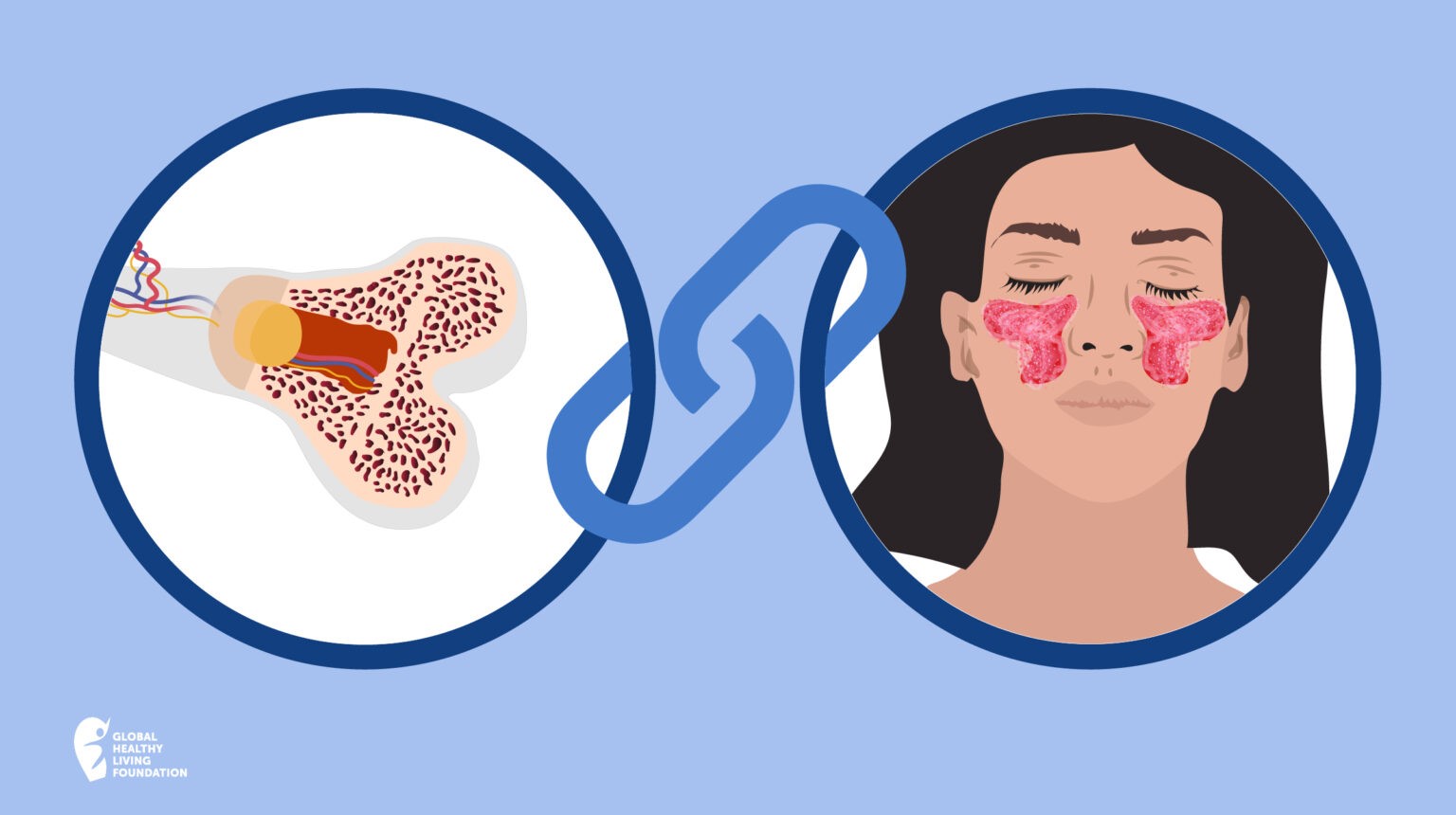

You can have different symptoms — from swollen joints to pain in your heels to fatigue — that doctors don’t realise are signs of PsA. Some PsA patients have traditional joint pain while others might complain more of enthesitis, or inflammation where ligaments and tendons connect to bones, such as at the heel or bottom of the foot.

Blood tests can be confusing

PsA patients often test positive for blood markers of inflammation, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). But psoriatic arthritis is considered a “seronegative” arthritis, which means that it doesn’t have telltale antibodies the way rheumatoid arthritis (RA) does with rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP. This can cause confusion between PsA and seronegative rheumatoid arthritis, in which RA patients don’t have these antibodies either. Seronegative RA occurs in 20 to 30 per cent of RA cases.

The Importance of Early Diagnosis

Given all these factors, it’s no wonder that a 2018 study conducted by our parent non-profit organisation, the Global Healthy Living Foundation (GHLF), found that 96 per cent of people who were ultimately diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis received at least one misdiagnosis first. For about 30 per cent of PsA patients, it took more than five years to get diagnosed.

These diagnosis delays could lead to irreversible joint damage, which is why it’s key to identify the problem early — and start treating it.

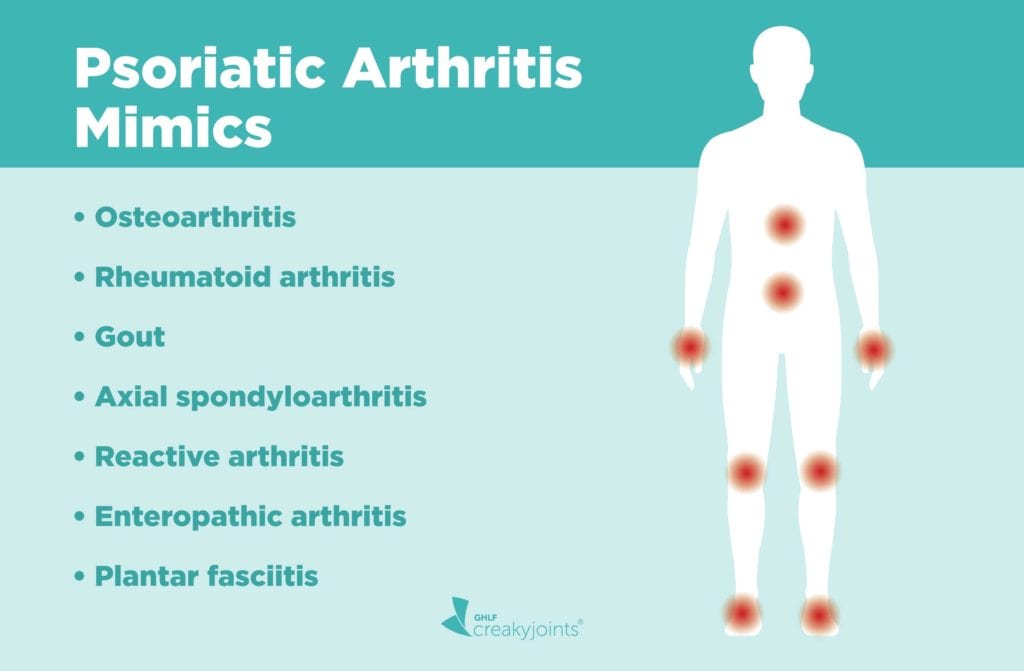

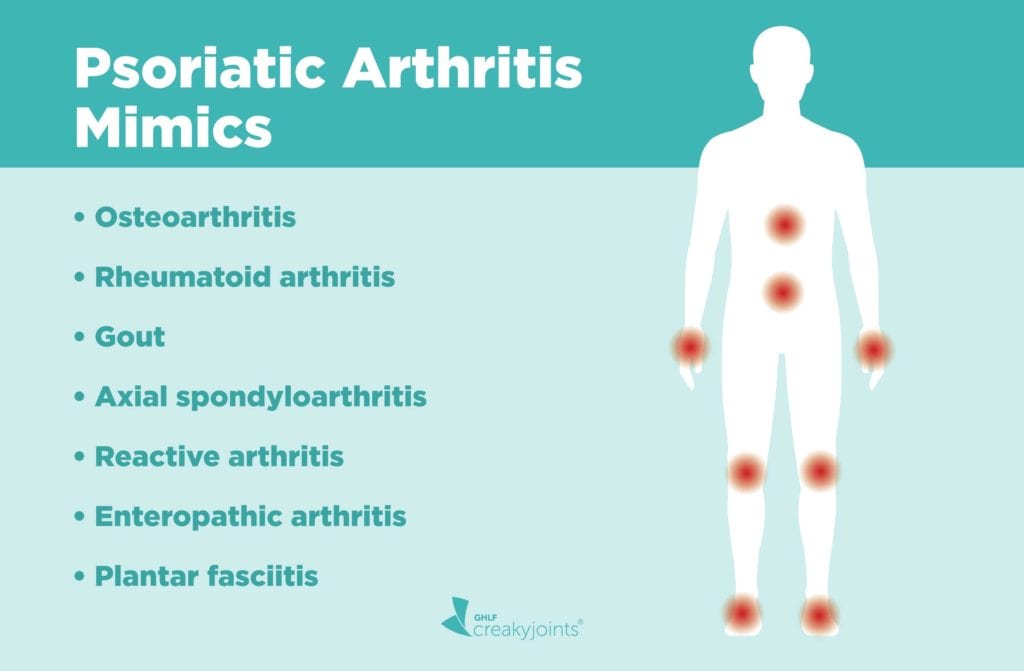

Here is a list of the most common health issues that can have symptoms that are similar to psoriatic arthritis. If you suspect you have any of them, share your concerns with your doctor or dermatologist and ask if further testing is right for you.

Osteoarthritis

In the GHLF study, 22 per cent of people with PsA said they were misdiagnosed with osteoarthritis. While some signs of osteoarthritis (OA) can be similar to those of PsA — swollen joints, pain and stiffness — people tend to develop osteoarthritis at older ages than they do PsA. However, previous injury to a joint may increase your risk of developing OA earlier.

Osteoarthritis is caused by mechanical wear and tear on cartilage and bones. The condition often appears gradually. Psoriatic arthritis, on the other hand, is an autoimmune disorder that is caused by an out-of-control immune system attacking the tissues around the joints.

The way specific joint symptoms manifest is usually different between OA and PsA. Take stiffness, for example: “Patients with PsA have a lot of stiffness. It usually happens in the mornings, and the stiffness will get better as the day progresses and as they start to use their body, like their hands or their back,” says Dr Haberman.

Patients with osteoarthritis may also feel stiff, but that stiffness tends to go away within 30 minutes, says Dr Haberman. In contract to PsA, osteoarthritis pain tends to get worse when you use your joints. For instance, if you have osteoarthritis in your knees, they’ll hurt as you go up and down the stairs.

Another difference is whether or when you get swelling in your joints. Tender, achy joints are common for patients with osteoarthritis — but generally, they tend to swell only when you overuse them. In PsA, you may wake up with swollen joints without having exerted yourself at all. “What I tell people is, ‘Listen, if you have knee pain after walking 10 miles (roughly 16 kilometres), you just overdid it. However, if you wake up with your joints red, warm and swollen, then we have a problem,’” Dr Domingues says.

Blood tests and X-rays can help distinguish inflammatory arthritic arthritis, like PsA from OA, as can joint fluid analysis. Osteoarthritis is typically treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) along with lifestyle changes, while PsA usually requires disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) to address the root underlying inflammation.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis are both autoimmune disorders that cause inflammation in the joints and throughout the body. Rheumatoid arthritis, like PsA, causes the synovial tissues that line the joints to thicken, causing pain, tenderness and swelling.

But while the symptoms can be similar, there can be distinct differences. “Rheumatoid arthritis is often symmetric, which means if you have it on one joint on one side, you often have it on the other side. Psoriatic arthritis is usually asymmetric,” Dr Haberman explains.

“Psoriatic arthritis often involves the most distal interphalangeal joints (or DIP joints — the joints closest to the fingernails),” she continues. “For example, on your hands, PsA affects the DIP joints, whereas rheumatoid arthritis in the hands often affects the more proximal joints — the middle joints in your hands and the knuckle joints.”

When these joints get damaged, it can show up in X-rays or on MRIs, which can provide more clues so a rheumatologist can distinguish between these two types of inflammatory arthritis, says Dr Domingues. “Rheumatoid arthritis typically doesn’t affect the distal interphalangeal joints, but that’s very common in psoriatic arthritis.”

Blood tests can often distinguish between RA and PsA as well. While both types of arthritis can cause inflammatory markers in your blood, patients with PsA typically don’t have the two antibodies that up to 80 per cent of patients with RA have — rheumatoid factor (RF) and cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP), according to a review study in RD Open.

If you are misdiagnosed with RA when what you really have is PsA, it’s good to know that some of the same drugs are used to treat both conditions, such as methotrexate and a few of the biologics, such as those in the TNF inhibitor class. The problem is that some RA-specific drugs may not be as effective against psoriasis plaques, and there are other types of biologic medications, such as IL-17 inhibitors and IL-23 inhibitors, that growing evidence shows are better suited to targeting psoriasis-related skin issues in addition to joint pain.

Gout

The prevalence of gout has been documented for thousands of years — even the ancient Egyptians made reference to it. This painful form of arthritis occurs when you have too much uric acid in your body, which then crystallises in and around the joints. The result: You wake up one morning with a red, swollen, painful finger big toe, though gout can affect other joints as well.

Like gout patients, people with psoriatic arthritis can also develop symptoms fairly quickly. PsA patients can also have just one swollen finger or toe (called dactylitis).

“We often call them ‘sausage digits,’” says Dr Haberman. “If that’s the only sign, a provider might say, ‘Oh, you just have one swollen joint. It’s your big toe. It’s probably gout.’”

Another source of confusion is that gout and PsA can co-exist. Patients who have psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis also tend to have higher rates of gout, too, according to Harvard research published in the journal Annals of Rheumatic Diseases.

A typical gout flare usually involves one or two joints and will go away on its own in about two weeks even if you don’t treat it, notes Dr Haberman. That’s not the case in psoriatic arthritis patients — dactylitis can take months to resolve.

Another key difference between PsA and gout: “When you have gout, the joint is much hotter, much more swollen and a lot more tender,” Dr Haberman explains. “So even putting a sheet over it makes it hurt intensely, which is not really the classic characteristics of dactylitis.”

To diagnose gout, doctors can analyse the fluid they’ve extracted with a needle from an affected toe or finger to see if it contains crystals of uric acid. They can also measure the amount of uric acid in your blood, although people with PsA and psoriasis can also have high uric acid levels.

Treating gout usually requires taking a uric acid-lowering medication to prevent future flares and joint damage, along with lifestyle changes such as weight loss or perhaps following a low-purine diet.

Axial spondyloarthritis

Back pain is one of the key features of axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) — a type of chronic inflammatory arthritis — since inflammation affects the vertebrate in your spine and the area where your spine meets the pelvis, called the sacroiliac joints. But back pain can also occur in psoriatic arthritis.

So what’s the difference between axSpA and PsA? They are both considered types of spondyloarthritis, which is a “family” of types of arthritis that have certain symptoms and genetic markers in common.

The genetic marker HLA-B27 is very common in people with axSpA; in some populations, as many as 90 per cent of patients with axSpA have it (though HLA-B27 is less common among African Americans and other groups). About 20 per cent of people with PsA are positive for HLA-B27.

Both PsA and axSpA can affect the spine as well as peripheral joints, like the knees and hips. PsA and axSpA patients can have enthesitis and dactylitis.

In “typical” cases, patients with axSpA present with lower back pain as their dominant symptom and patients with PsA present with peripheral joint pain as their dominant symptom, but for some people, the distinctions are not that black and white.

For example, according to a study in the journal Nature Reviews Rheumatology, isolated spondylitis, or back inflammation, occurs in 5 per cent of PsA patients, while psoriasis also occurs in about 10 per cent of patients with axSpA. And many people with axSpA go on to have peripheral joint pain.

If this all sounds confusing, that’s because it is. In fact, experts are still debating whether psoriatic arthritis with axial (spine) symptoms and axSpA “are separate entities with overlapping characteristics, or whether they represent different clinical presentations of the same disease,” according to an article in Rheumatology Advisor.

While research does seem to indicate that there are distinct differences in axSpA patients who have psoriasis and PsA patients who have lower back pain, it’s easy to see how diagnosing one from the other could be tricky depending on which sets of symptoms patients are complaining about.

There is overlap between treatment for both conditions, such as anti-TNF biologics and IL-17 inhibitor biologics. But treatment can differ in many cases. For example, conventional DMARDs like methotrexate can treat peripheral joint inflammation — and are commonly used in psoriatic arthritis — but they cannot treat axial symptoms.

That’s why “it is important for rheumatologists to make the right diagnosis and follow and treat patients accordingly,” University of Toronto rheumatologist Dafna Gladman, MD, told Rheumatology Advisor.

To make the right diagnosis, doctors look for the most salient clinical features of PsA, including skin psoriasis, as well as use X-rays and even MRIs to look for evidence of the types of damage and inflammation, says Dr Haberman.

Reactive arthritis

Reactive arthritis is also a type of spondyloarthritis. It is triggered by a bacterial infection from such bacteria as campylobacter, chlamydia, salmonella, shigella or yersinia, which are typically either sexually transmitted or digested from food. These germs are very common, and most people who are exposed to them will not develop reactive arthritis. But for a small group, who likely are genetically predisposed, becoming infected with these bacteria causes the immune system to react in a way that also causes joint pain and other symptoms.

Reactive arthritis can look similar to psoriatic arthritis in that both conditions can cause asymmetric joint pain, especially in the lower limbs, back pain, enthesitis and dactylitis. But the defining factor for reactive arthritis is symptoms or a history of infection. Reactive arthritis also tends to cause eye inflammation (eyes will look red, watery and irritated) and inflammation in the urinary tract (which can make going to the bathroom painful).

Doctors won’t necessarily rule out reactive arthritis if there’s no sign of triggering bacteria (the infection could clear while other symptoms persist), but involvement of the eye or urethra tend to point to reactive arthritis.

Arthritis related to inflammatory bowel disease

Arthritis can also be a co-occurring disease in inflammatory bowel diseases like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. This kind of arthritis, also a type of spondyloarthritis, is called enteropathic arthritis. The pattern of symptoms can be very similar to that of PsA, including asymmetric joint pain and lower back pain. Psoriasis can also co-occur in people with inflammatory bowel disease, which makes separating PsA from IBD-related arthritis even more confusing.

But usually, people with IBD-related arthritis do not have the nail changes characteristic of PsA. The “distal” joints of the fingers — the ones closest to the fingernails — also tend to not be affected in IBD-related arthritis.

Plantar fasciitis

Plantar fasciitis — inflammation of a band of tissue that runs across the bottom of your foot, causing heel pain — is technically considered a symptom of psoriatic arthritis.

In most cases of plantar fasciitis, the inflammation occurs because of repetitive stretching or stress on the area, such as physical activities that put a lot of stress on your heel, being obese or having a job that keeps you on your feet for most of the day. But in PsA, plantar fasciitis also happens because of dysfunction with inflammation related to your immune system. This causes enthesitis — or inflammation where ligaments (in this case, the plantar fascia) attach to bone.

In one study of PsA patients from Dr Gladman at the University of Toronto, 35 per cent had enthesitis and the plantar fascia was among the three most common sites.

The problem is that many people who experience heel pain seek treatment at a podiatrist or other health care provider and they don’t think to suspect PsA (or another kind of spondyloarthritis, such as axSpA) as a potential root cause.

If you’re being treated for plantar fasciitis and the condition isn’t getting better or keeps re-occurring, consider the other symptoms and domains of psoriatic arthritis (such as a history of psoriasis, joint pain or fatigue) and ask your doctor whether further testing, including blood tests and X-rays, is warranted.

Getting to the Bottom of a Psoriatic Arthritis Diagnosis (Or Something Else)

Getting a proper PsA diagnosis depends on so many things, including seeing a savvy provider who spends the time to take a comprehensive medical history. “The history is really definitive,” explains Dr Domingues.

That means a doctor will probably ask you if you have or ever had psoriasis. This is the time to mention any itchy, flaky spots, even if you’ve always thought you just had dry skin. The provider should also ask about any first-degree family members — a sibling or parent — who might have had psoriasis because you can be diagnosed with PsA with a family history of the condition, Dr Haberman explains.

The doctor will also examine your nails and toenails because they can be affected by psoriasis, even though it’s not obvious. Some signs include nails that are pitted or have ridges, are discoloured or look like they’re crumbling and separating from the nail bed.

Then the doctor will ask you about your joint pain (how much stiffness, where you have pain) as well as do a thorough physical examination. Blood tests can reveal inflammatory markers (and distinguish between the different types of arthritis) and X-rays and other imaging tests can show joint damage and inflammation in the joint.

If you are having any aches and pains and you think or know you have psoriasis, don’t write off your symptoms. Instead, ask your provider to refer you to a rheumatologist, which is the best type of provider to determine if you have PsA or another condition.

“We’re more than happy to see patients, and we’d like to see them early,” says Dr Haberman. “Even if we say, ‘This isn’t psoriatic arthritis yet,’ it also gives us a chance to educate patients on what they should look out for in the future, because psoriatic arthritis can develop years after a psoriasis diagnosis.”

This article has been adapted, with permission, from a corresponding article by Linda Rodgers on the CreakyJoints US website. Some content may have been changed to suit our Australian audience.

Keep Reading

- 10 Things to do After an Arthritis Diagnosis: Top Tips From Patients

- A Patient’s Guide to Living with Axial Spondyloarthritis in Australia

- A Patient’s Guide to Living with Rheumatoid Arthritis in Australia

- Patient Stories

- Living With Arthritis During COVID-19: Education and Support Resources

Sources

Axial Psoriatic Arthritis and Ankylosing Spondylitis: Comparing Clinical, Radiologic Characteristics. Rheumatology Advisor. https://www.rheumatologyadvisor.com/home/topics/spondyloarthritis/axial-psoriatic-arthritis-and-ankylosing-spondylitis-comparing-clinical-radiologic-characteristics. Published January 12, 2019.

Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis. UpToDate. 2019. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-psoriatic-arthritis.

Feld J, et al. Axial disease in psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: a critical comparison. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. May 2018. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-018-0006-8.

Gout. American College of Rheumatology. https://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Gout.

Gout. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/gout/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20372903. Published March 1, 2019.

Interview with Rebecca Haberman, MD, NYU Langone Health

Interview with Vinicius Domingues, CreakyJoints medical advisor

Merola JF, et al. Distinguishing rheumatoid arthritis from psoriatic arthritis. RMD Open: Rheumatic & Musculoskeletal Diseases. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000656.

Merola JF, et al. Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and risk of gout in US men and women. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. August 2015. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205212.

Ogdie A, et al. Diagnostic experiences of patients with psoriatic arthritis: misdiagnosis is common. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. June 2018. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-eular.4374.

Osteoarthritis. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/osteoarthritis/symptoms-causes/syc-20351925. Published May 8, 2019.

Polachek A, et al. Clinical Enthesitis in a Prospective Longitudinal Psoriatic Arthritis Cohort: Incidence, Prevalence, Characteristics, and Outcome. Arthritis Care & Research. 2016. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23174.

Reactive Arthritis. American College of Rheumatology. https://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Reactive-Arthritis.

Rheumatoid Arthritis. American College of Rheumatology. https://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Rheumatoid-Arthritis.

Spondyloarthritis. American College of Rheumatology. https://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Spondyloarthritis.

Villani AP, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. August 2015. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2015.05.001.