Disclaimer

This information should never replace the information and advice from your treating physician. It is meant to inform the discussion that you have with healthcare professionals, as well as others who play a role in your care and well-being.

Access to opioid medications

As you may know, the Australian regulations surrounding access to opioid medications have changed.

In December 2016, the Federal Government passed new legislation restricting over-the-counter (OTC) access to all medications containing codeine (a form of opioid medication). This legislation will come into effect next year. Currently, medications that contain up to 30 mg of codeine can be bought without a prescription from pharmacies and supermarkets. This includes drugs such as Panadeine, Nurofen Plus, and Mersyndol.

However, from February 2018, ALL medications containing codeine will need a prescription from a qualified doctor. See our article How the changes to codeine prescription regulations in Australia will affect you for more details on why this change was viewed as necessary.

For many people, this new requirement will mean rethinking their pain management strategy as they may not be able to get to their GP easily or they may not be able to use other OTC pain-relieving medications. Others have already been accessing higher-dose codeine medications on prescription but the controversy surrounding its use have made them rethink its place in their pain-management regime. (I’m one of them!)

Even if you don’t use codeine-based medications, you might still be interested in learning about drug-free ways to manage your pain.

I’ve always complemented my medications with other forms of pain-relief (including heat packs, massage, and stretching) and I’m continually on the lookout for more options to add to my tool kit. I’ve become increasingly intrigued by the role of the brain in how we experience pain and how we can harness its power to help lessen the effect that pain has on our daily lives.

I’ve compiled a list of strategies that I’ve either tried and loved or am keen to explore. But first, let’s look at how pain works.

Understanding pain signals

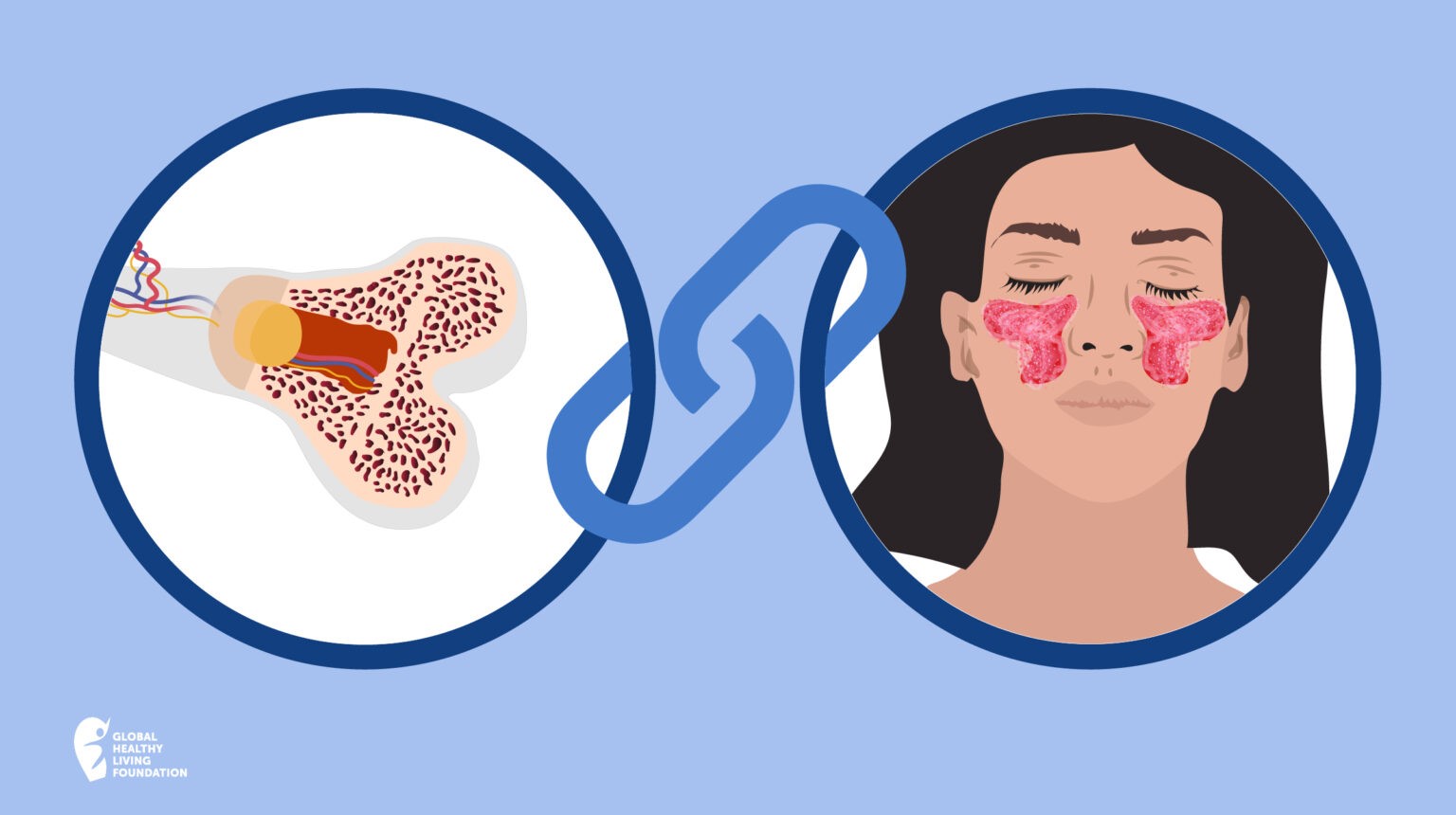

When we injure ourselves or experience discomfort in some way, our body sends chemical signals (called neurotransmitters) via our nerves from the injured site to the brain as an alert to say “There’s something wrong! Do something! Now!” Once the signal reaches the brain, the brain processes it along with any input it receives from our other senses to assess the degree of danger and select an appropriate action.

The fascinating thing about our experience of pain is that it doesn’t come from the injured tissue. That signal simply tells the brain that something has happened to the tissue. It is only when the brain assesses the whole situation that it decides (subconsciously) whether or not to associate the feeling of pain with the injury.

There are times when it might not associate any pain at all, such as when it is too busy helping the body compete in a high-intensity sporting event. We’ve heard stories of runners winning marathons with their feet torn to shreds because they never felt the stone in their shoe. Or the footballers finishing a game only to learn later that they had broken a finger or cracked a rib and not felt a thing.

In some people, the signal from the damaged tissue doesn’t get through to the brain, so they don’t experience any pain, even when the damage is quite extensive. This can happen in people with severe diabetic neuropathy, for example. When the nerve cells in their feet become damaged or even die off, they lose sensation in their feet and may fail to notice when they’ve stepped on a nail. If they don’t check their feet regularly, injuries like these can quickly become infected and cause further problems.

Sometimes, the brain can misinterpret signals and generate pain levels that are out of proportion with the initial injury. Or, the nerves in the tissue area might send far too many signals to the brain. It might not even be an injury that triggers the signal. It might just be the touch of fabric against the skin or the pressure of a hug. This is one of the symptoms that some people with fibromyalgia experience.

In short-term (or acute) pain, the pain subsides once the trigger signal has stopped and the wounded area has mostly healed. However, sometimes the signal doesn’t switch off so the brain continues to generate the experience of pain long after the body has healed. This is known as chronic pain.

None of this means that pain is ‘all in the brain’. Pain is real, it’s just that the messages can get trapped in unhelpful loops and detours.

Professor Lorimer Moseley is a Professor of Clinical Neurosciences and Chair in Physiotherapy at the University of South Australia. He is one of the world’s leading experts in pain sciences and is passionate about helping people to understand and manage chronic pain. In his TEDx Adelaide talk ‘Why Things Hurt’, he discusses how we experience pain in engaging and easy-to-understand terms.

Learning to ‘re-think’ pain messages

Whenever we learn something new, we form new neural pathways between different parts of the brain. These pathways form intricate connections and the more exposure we have to each new thing, the stronger the connections become.

Pain signals are processed in multiple areas of the brain and each of these parts also carry out other functions. For example, some pain signals are processed in the same areas that process our senses, memories, emotions, and movements. When chronic pain signals dominate brain activity in these areas, the other functions can become harder to control. This explains why it can be very hard for us to concentrate while in pain.

In recent decades, scientists have discovered that it is possible to block, and even reverse, unhelpful neuropathic connections – including those that keep chronic pain signals firing. Although the theories and methods differ, they all involve changing how information is processed between the mind and body.

This information processing is a two-way street. It can happen from the top down – where an action begins with a thought and the signal gets passed down the body to the relevant areas. Or the signal can travel from the body to the brain, telling it to act.

Some re-programming techniques start with the mind, encouraging us to change how we think about pain while others use the body to send new signals to the brain with the aim of reducing or replacing the unhelpful signals.

I’ve included a mix of both approaches as we are all unique and some techniques may work better for us than others.

Pain management strategies that harness your brain power

Virtual reality

Using VR to treat chronic pain is a relatively new practice but the long-term signs look promising. In these settings, participants wear virtual reality goggles and have motion-controlled sensors strapped to their body. Through the goggles, they see a virtual version of their own body in different settings.

VR works by fooling the brain into believing that the areas where the person had been experiencing pain now function normally. For example, a man with chronic pain in his left arm had his VR experience customised so that when he moved his ‘real’ pain-free right arm, he saw his ‘virtual’ left arm moving effortlessly.

With repetition, the man’s brain began to believe his left arm could function normally so when he did move it, he experienced far less pain. While this not yet a common treatment for chronic pain, it could well be in the near future.

More information:

Research into VR for chronic pain management is still in its very early stages. Angela Li, Zorash Montano, Vincent Chen, and Jeffrey Gold have summarised much of the current research in their paper for the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), Virtual reality and pain management: current trends and future directions.

Immerse yourself in meaningful activities

Many people find distraction is a great way to relieve their pain. When they become engrossed in an activity, especially a creative one, their narrow focus helps them to forget they are in pain. It doesn’t stop the source of pain, but it gives the body a chance to rest and recuperate for a while.

Watching a movie, reading a book or chatting with friends can all be excellent forms of distraction.

Music and art therapies can help us manage our pain in two ways. They can be used as forms of distraction – where we get so caught up in the process of creating or participating in something that pleases us, we pay less attention to our pain. We use the sections of the brain that process our pain to process the things we see, hear, touch, and even taste and smell in relation to our art instead, so the pain signals get overpowered.

These therapies also help by providing us with outlets to express the emotions we hold in relation to our pain. Sometimes these emotions (such as anger, fear, and guilt) can be difficult to put into words but we can express them through painting, making music, and similar activities.

Find a practitioner

Australian and New Zealand Arts Therapy Association (ANZATA)

Australian Music Therapy Association

Hypnotherapy

When you saw the word’ hypnotherapy’ what did you think? Did you have an image of an aging practitioner in a consulting room getting the client to follow the movements of a swinging stop watch just with their eyes? Did you see someone up on stage putting another person into a trance, then getting them to do all sorts of strange acts? Did you think it was all a load of nonsense?

The reality is that hypnotherapy is a common treatment used by many clinical therapists and other qualified professionals to help those with negative subconscious thought patterns to break free of them. It is a heavily-researched area with a high success rate, however (like many forms of treatment) it doesn’t suit everyone.

During a session, the therapist will guide you into a trance-like state using verbal or visual repetition. You will feel deeply relaxed but you are fully awake at all times – much like the ‘daydream’ state you can slip into when doing a monotonous physical task. In this state, your subconscious and conscious minds are both active. It is not possible for anyone to get you to do anything against your will while in this state. If your conscious mind senses a conflict or potential danger, it will make you fully alert instantly.

It is the subconscious mind that holds onto old or unhelpful belief patterns like “That hurt when I did it last time so I know it’s bound to hurt again”. However, when you are under hypnosis, your therapist can make alternative suggestions to your subconscious mind such as “The pain didn’t last long last time and I coped well with it, so I know I’ll be ok this time”.

According to Jenny Nash in her article ‘Hypnosis for Pain Relief’ for the Arthritis Foundation:

“Hypnosis isn’t about convincing you that you don’t feel pain; it’s about helping you manage the fear and anxiety you feel related to that pain. It relaxes you, and it redirects your attention from the sensation of pain.”

Hypnosis is always best done with a qualified practitioner.

Find a practitioner

Australian Hypnotherapists Association

Mindfulness

You’ve probably heard the term ‘mindfulness’ plastered everywhere, from your favourite magazines to your Facebook newsfeed. There are even mindfulness colouring books for adults. Because of all this publicity, you might have come to believe that it is just hype and that there is no substance to it.

The truth is that mindfulness has been proven to help with a range of issues such as anxiety, addictions, insomnia and chronic pain.

To understand the concept of mindfulness, it helps to compare it to mindlessness. Imagine that you are reading a book and slowly drifting off to sleep. As you tune out, you read the same page over and over without taking anything in. In that state, you are awake but your conscious mind has zoned-out.

In a state of mindfulness, on the other hand, you are fully awake and aware of everything around you. You are simply calm enough to observe it all without any emotional attachment or judgement.

For example, pain often comes with lots of emotions attached, but while practicing mindfulness you can observe the pain and the thoughts that arise without responding to those thoughts in any way. Some people describe it as looking inside their mind through a window. They can observe their thoughts and feelings with curiosity but without being immersed in them.

Some of the thoughts we attach to chronic pain can make the pain worse. We might say to ourselves things like:

- “Every time I use the stairs, my knees scream in pain”

- “I hate being in pain but it never ends”, or

- “This pain has ruined my life”.

When thoughts like these buzz around in our head, we can become even more frustrated and overwhelmed which forces our heart rate up and we start to breathe more rapidly. Not surprisingly, this increased stress turns the pain intensity up further and we get locked into an endless cycle. To break it, we need to remove ourselves from as many stressful distractions as possible.

If you can’t put yourself in a quiet and comfortable place physically, try tuning out by using headphones and playing some calming music, then closing your eyes. Pay attention to your breathing but don’t try to control it. Just notice the feeling of the air as it passes in through your nose and out through your mouth.

One effective mindfulness technique is to wait until your breath has slowed down a bit and then briefly notice any parts of the body that are in pain. Notice the thoughts that drift through your mind and then let them go. Keep breathing evenly with your eyes closed and then shift your focus to a part of your body that feels fine. Notice any new thoughts that arise, but again, don’t judge them. This may be tricky at first as the pain areas demand more attention, but ignore them and scan through your body to find areas that aren’t in pain.

With regular practice, many people find that it becomes easier to notice the pain-free areas and that the negative thoughts attached to the painful areas become less intense. As a result, the pain experience itself becomes less intense. The pain source or injury may still be there, but it’s impact on our state-of-mind is reduced. Our negative thoughts and feelings gradually become replaced by neutral or more positive ones.

Susan Bernstein’s article ‘Ease Arthritis Symptoms with Meditation’ on the Arthritis Foundation website offers a more detailed explanation of mindfulness and outlines the scientific research that proves its effectiveness for chronic pain relief.

Find a practitioner

Natural Therapy Pages

Tapping therapy

Tapping therapy may possibly be one of the most effective drug-free pain-relieving techniques you’ve never heard of. The best part is that it can be done in minutes!

Clinical psychologist, Dr Roger Callahan, developed his Thought Field Therapy (TFT) in the early 1980’s. This approach combines aspects of modern psychology, Chinese acupuncture, kinesiology, neurolinguistic programming, and even some quantum physics. It has been proven to help treat a variety of conditions including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), addictions, and chronic pain. One of Callahan’s students, Gary Craig, developed his own variation of tapping called Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT), which is also widely used.

Although TFT and EFT have been practiced by many health professionals for decades, they are only slowly creeping into mainstream awareness. Annie Hlavats lists several EFT research studies in her LinkedIn article The Link Between Stress, Trauma and Chronic Pain.

Australian clinical and health psychologist and Associate Professor in Psychology at Bond University, Dr Peta Stapleton, is leading the way in research on EFT for weight management and chronic pain. If you’d like to see more evidence-based research about this therapy, the EFT research bibliography lists more than 100 papers published in peer-reviewed professional journals.

So, what is it, exactly?

The technique involves using the fingers to gently, but firmly, tap on the body’s pressure points located at the junction of the meridian (or energy) lines used in acupuncture and other traditional healing systems. You can learn to use tapping on yourself or you can seek a qualified practitioner to help you.

When we are tense for long periods, our muscles contract and can get locked in a kind of seizure. This causes tension to accumulate around our pressure points – rather like the pressure created by river dams. Tapping on these points releases the stored-up tension like flood gates opening.

As the tension is released, our muscles relax; sending endorphins around our body and allowing our fresh, oxygenated blood to flow more freely. This, in turn, flushes out stored toxins.

As with hypnotherapy and mindfulness, tapping requires us to think about our pain differently. Tapping alone is only part of the treatment. We need to identify any negative thoughts or emotions connected to our pain first.

Before beginning a tapping sequence, you need to intentionally think about the pain or problem that you’d like to address, then rate its intensity on a scale from 1 to 10 (with 10 being the greatest intensity). You then tap the pressure points (or a sequence of points) for around 5 – 30 seconds and rate the intensity of the issue again. Some issues may only take a few sets like this to clear the issue, while more deep-rooted issues may take longer.

According to Underground Health Reporter:

“While tapping and the use of “energy systems” in general is somewhat new to the Western world, it has been practiced in Eastern medicine for over 5,000 years and is poised to revolutionize modern medicine. Already, tapping/ EFT therapy is used and recommended by leading experts such as Jack Canfield, Joe Vitale, Cheryl Richardson, Deepak Chopra, Dr Joseph Mercola, Kris Carr, and a growing number of other prestigious health pioneers.”

Find a practitioner

EFT Australasian Practitioners Association

EMDR

Eye Movement Densitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) is an evidence-based practice used by mental health professionals around the world. It focuses on the physical, mental, and emotional impact that our memories have on the brain.

The therapy is based on the principle that some distressing or traumatic events may overwhelm our normal coping mechanisms, including our brain’s information processing system. Our memories of these events (along with our memories of the associated sounds, sights and other stimuli) get stored in an isolated memory network where they remain ‘stuck’. Any irrational beliefs or negative behaviours associated with these unprocessed memories are symptoms of those memories so treating them in isolation is less effective than removing their underlying cause.

The therapy uses a systematic approach to engage the brain’s natural information processing system and reduce the enduring effects of the unprocessed memories and relieve current symptoms.

During an EMDR session, the client will be asked to recall and describe any spontaneous associations of traumatic images, emotions, physical sensations, and thoughts while simultaneously following the movement of the therapist’s hand or wand from side to side in a brief rhythmic pattern.

This side to side eye movement is itself a form of bi-lateral stimulation – forcing both sides of the brain to focus on a particular activity at the same time. (For example, focusing on the physical sensations that arise while clapping or patting the right and left knees.) Bi-lateral stimulation on its own is known to have calming and pain-relieving effects, but when it is combined with memory recall and conducted in defined sequences it is far more effective. While any individual can perform bi-lateral stimulation on themselves, EMDR can only be conducted by a trained therapist.

EMDR was originally developed by Francine Shapiro to treat PTSD but it has since been proven to be effective on a range of other physical and mental health conditions, including chronic pain.

EMDR cannot undo any physical causes of pain, but it can reduce (or even eliminate) our awareness of pain so that we can concentrate on other things more easily or put the thoughts that surround our pain into a more rational perspective. The pain might still be there as a kind of ‘background noise’ but it is no longer as important or all-compassing.

Find a practitioner

The EMDR Association of Australia

These strategies are only a small sample of all the drug-free pain management options we all have available to us. You may also like other approaches including physiotherapy, hydrotherapy, massage, tai chi, cognitive behavioural therapy, myopathy, and more.

Experiment to see which approaches suit you. You may find that you get best results from using a combination of approaches.

Disclaimer

This information should never replace the information and advice from your treating physician. It is meant to inform the discussion that you have with healthcare professionals, as well as others who play a role in your care and well-being.